RESOURCE LIBRARY

A collection of resources for civic leaders in Europe and the US committed to building a bigger “we”.

“In a 2024 podcast interview with Joe Rogan, Mark Zuckerberg mentioned that corporate culture in America is neutered, taking the grandstand view that the workplace needs more “masculine energy.” At the time, in some circles, Zuckerberg’s comments were the source of both outrage and mockery (I will admit I much laughed). But since then, a more intellectualized version of that idea—one that has always lingered in the background—has started to gain ground in North American and European cultural discourse. What once lived in conservative or fringe think tanks and conferences has seeped into the mainstream and even pop culture. Most recently, Helen Andrews made the case in a New York Times podcast and op-ed with Ross Douthat, claiming that companies and institutions now have “too many women,” a shift she says threatens civilizational decline.”

At its heart is a monthly Goûter — an afternoon tea where elders and younger generations meet. Elders share life histories, knowledge of the landscape, and memories of the villages. The aim is to uncover stories that have shaped the territory and explore how they connect to our shared present. These dialogues build empathy and understanding, moving beyond political and cultural divides.

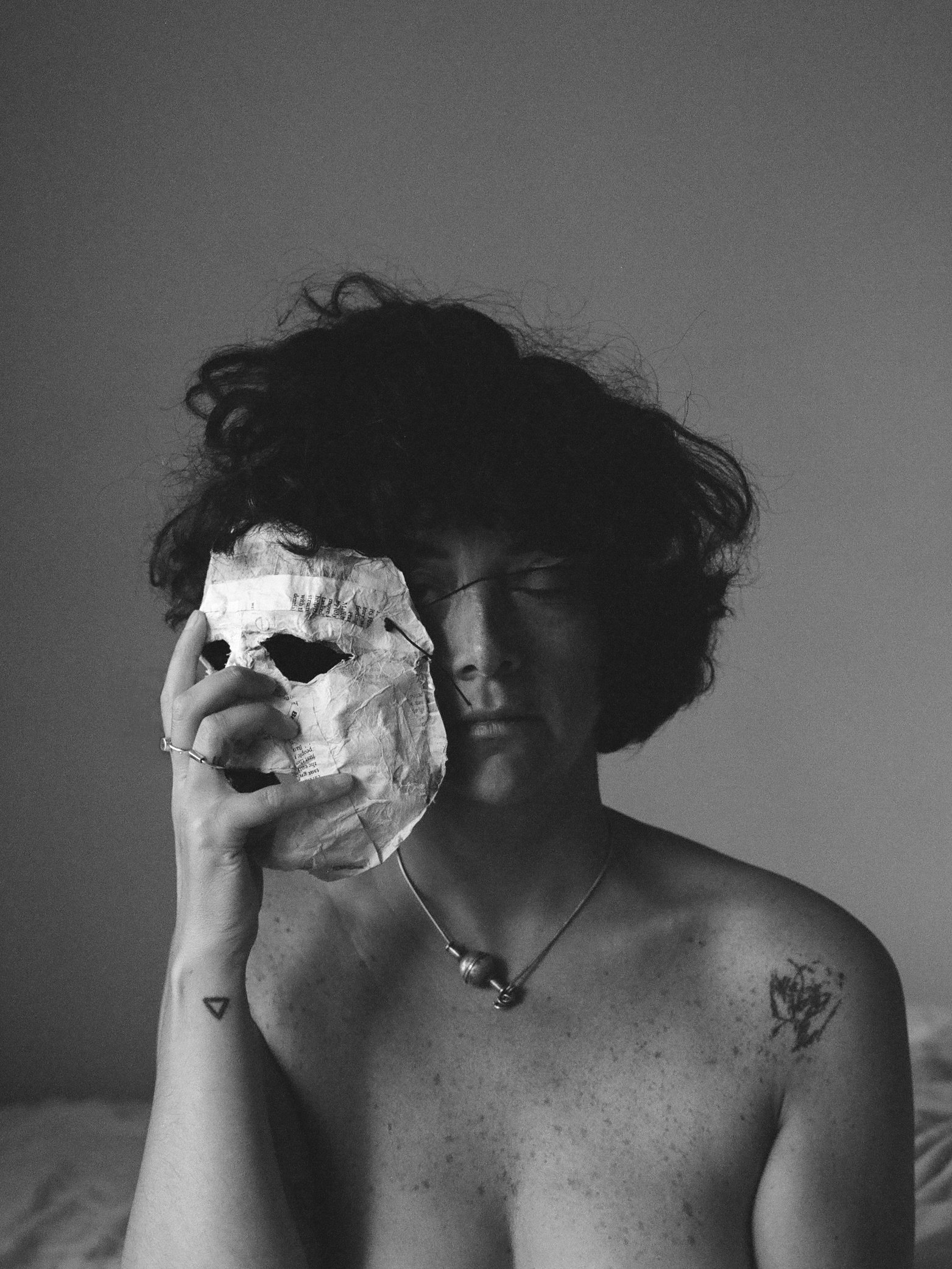

One key dimension of belonging in cities we try to explore is how to create the conditions so people within communities feel like they have the power and capacity to contribute; to see themselves as protagonists who can shape their own cities or neighborhoods. Such exploration sometimes means creating space for reflection, which takes time to foster so people can share openly in the space.

The opportunity that ‘Coming Home’ addresses is the human capacity for listening, which is fundamental to bridging, belonging, and democracy. Listening is the mindful receptivity that precedes action. If we do not make space for these momentary pauses to notice our own listening, then we end up recreating the past on autopilot. For society at large to shift, we must make the study and practice of (open, nonjudgmental, clarifying) listening commonplace.

Changes in the political order—globally and nationally—are part and parcel of human history. In 2025, the process of becoming less and less inclusive and democratic is seemingly leaving no country unscathed. The arc of history is bending in the direction of othering and continued oppression. According to V-Dem, 2025 marks the 25th consecutive year of autocratization (that is, of the world becoming even less democratic). For the first time in 20 years, there are more autocracies than democracies, and if I am not mistaken, this just considers two regime types, leaving aside those that can now be considered mixed models, democratic in form, authoritarian in many practices. As IDEA’s team reports in The Global State of Democracy, “Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation—the four pillars of democracy—are under strain, with unprecedented global declines in judicial independence, press freedom and electoral integrity.”

For the past ten years or more, I’ve had the sense that debates on migration policy keep looping back on themselves, like a political Groundhog Day–at least, on the surface. Amongst most of the political leadership in Europe and North America, the predominant themes, once the remit of far-right politicians, seem to stay the same: securitization, outsourcing, deportation. That, when not outright vitriol and cruelty. Meanwhile, public opinion is often treated as if it is always hostile, even though the evidence shows us that on migration, as on many other topics, public opinion can shift significantly.

How is it that despite significant evidence of corruption, crimes, or illegal acts, these political actors still manage to muster the support of a public driven by anti-corruption and anti-establishment sentiment?

Authoritarian populist actors function like a multi-headed hydra in constant movement, and it is in part the internal diversity of the many “heads” that gives it its strength—but could also become its undoing. Despite somewhat different ideological goals, a broad coalition of interest groups (including white supremacists, Christian nationalists, tech oligarchs, anti-gender activists, ecofascists, and so on) has come together, both nationally and transnationally, realizing that their shared goals are more achievable if they join forces and change the political order together.

But not all heads of the hydra wield equal force. Tech oligarchs—especially Elon Musk—have acquired a distinct role, both in the US and globally, suggesting that their priorities may ultimately take predominance over those of their allies, which could eventually lead to conflict, fragmentation, and the breakdown of the authoritarian populist coalition. As tech billionaires take on a more central role, they may become a liability for authoritarian populist politicians. These leaders risk losing their credibility as champions of "the people" against the elites—even if that stance was always a pretense.

Over the summer, right after the EU Parliament elections, one of the emergent narratives was that the center had held, despite the success of authoritarian populists in the election, and that the joining of forces in France could provide an alternative to Marine LePen’s party. A few months later, what we see is that in the EU institutions, rather than mainstream partners voting in block to act as a counterbalance to extremist forces, they have now become comrade in arms. After dubious political maneuvering by French president Emmanuel Macron, just this December the French government collapsed, making a new far-right government in the next election even more likely (Macron has just appointed a new prime minister, the fourth PM this year). Similarly, there was momentarily a barrage of commentary about Trump winning by a landslide in the US. Looking at the data once the full results were publicly revealed, it is clear that his victory was in fact not a landslide, especially when viewed from a historical perspective.

Which stories make sense, which need to be more closely examined, or complexified, and which ones we tell ourselves because they make us feel better thus need to be interrogated.

Through the lens of the framework of authoritarian populism, the framing of left vs right is deemphasized, focusing instead on the interplay of the populist and authoritarian playbooks—a dance between rhetorical claims to speak in the name of the people against the elites with anti-democratic practices—deployed in pursuit of nativist and exclusionary goals (economics, foreign policy, and other policy-areas become subordinate to these two orienting objectives). This shift in focus can also help us make sense of the global structures of cooperation or imitation of authoritarian populists, which deploy similar narratives and policies across countries and share financial and other resources despite historical, socioeconomic, and even ideological differences.

Times appear to be changing as the European periphery seems to be leading the way to a social Europe, or at least strongly advocating for one; trying to make sure that policies are accompanied by belonging narratives that can deactivate the impulse to other. These policies and narratives should make clear that the Union may be in the making, but citizens from all Europe are in it together and the future of Europe depends on how much they feel they belong. For that, you also need the periphery (and its peripheries) to feel included and this is probably the next and most pressing challenge.

It’s time to look beyond a limited concept, that obscures at least as much as it reveals.

To go beyond polarisation as a concept, we need to transcend its limits - by using a more contemporary and nuanced psychology to connect the varied social trends of recent decades - including technological and media change - with the range of major social challenges that have come to the fore in that time.

With a broader lens like this, we might start to see the real root causes in our common social ills, how they are connected–and what would be necessary to truly address them. Polarisation cannot offer us that–but we have the tools to begin creating something better that can.

“Othering'' in this context, against LGBTQ+ persons and groups, basically reduces people to some abstract, undefined “ideology.” Belonging, on the other hand, is formed in solidarity practices – in the discussions and support actions around the “Atlas of Hate," in various queer and LGBTQ+ marches in big and small towns of Poland, and in legal and media support. In some municipalities, like those of Poznań, Warsaw, and Gdańsk, the solidarity of opening the “LGBTQ+ - zones” was emphasized with actions like the huge Palace of Culture in Warsaw bearing the rainbow colors in the Pride month and on other occasions.

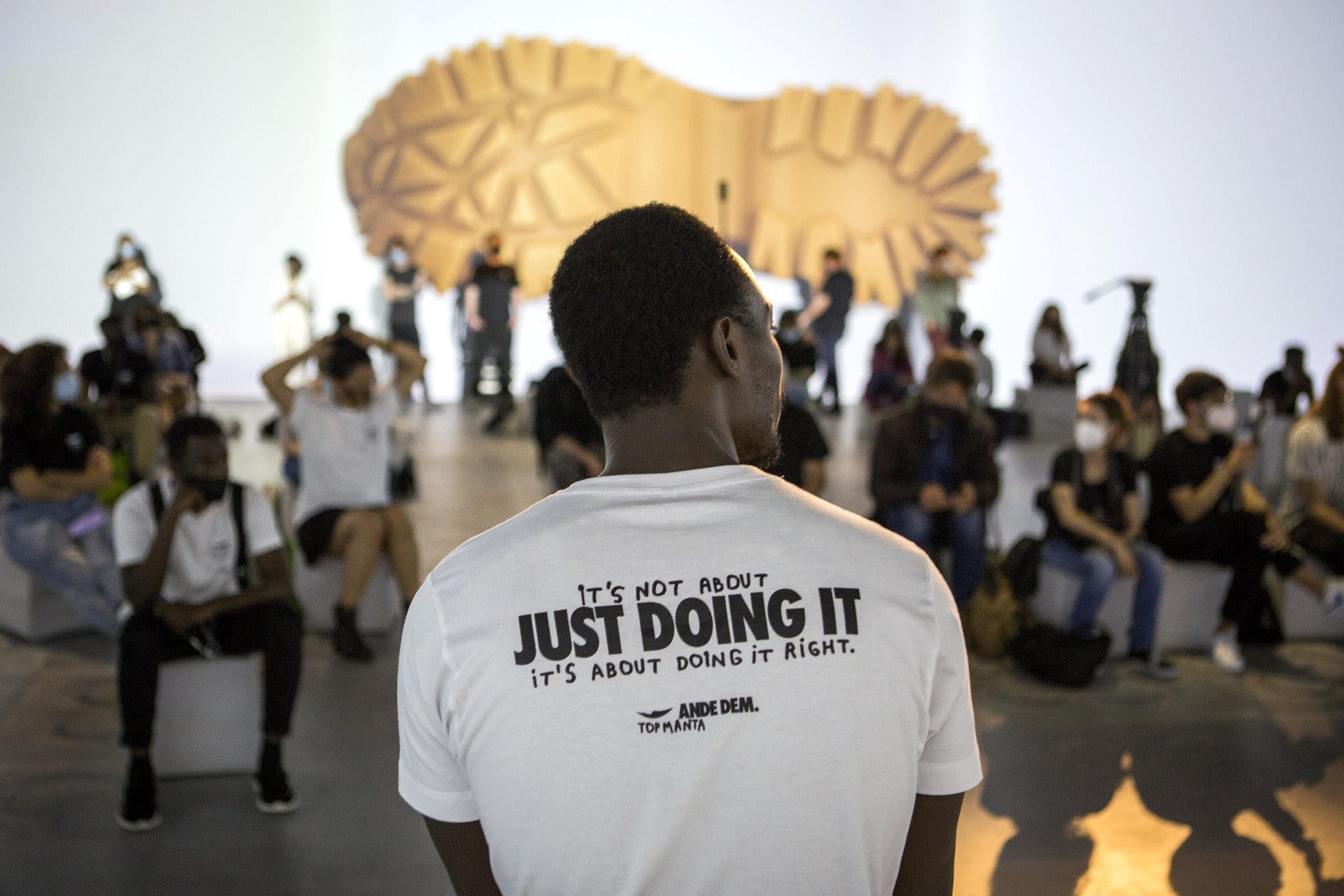

The success of Top Manta is a rebuke to Spaniards who think African immigrants do not belong. It has proved that it is much more than just a clothing brand. It is a movement–and one that is spreading to other cities; street vendors have opened a store called Pantera in the neighborhood of Lavapiés in Madrid. The store offers a solution to escape criminalization and precariousness while transforming and dignifying the meaning of the pejorative term.

My overriding sense after seven years of working with these ideas, and particularly having enriched my understanding further by integrating them with those of the Othering and Belonging Institute, is an ever deeper conviction that the current state of play cannot hold for much longer. Britain will either step into the Citizen Story, embracing the truth that all of us are smarter than any of us and the tools that allow that truth to be turned into action, or - as happened after the hopeful, visionary moment of the Putney Debates - this country will return to a state of oppression, othering, and subjection.

I know which future I am working for.

We define radical kindness as a type of kindness that reaches out across differences and may involve some form of disruption, discomfort, or transformation. It is distinct from random and relational acts of kindness, which tend to be carried out towards those who people perceive as belonging to the same group as themselves. In contrast, radical kindness refers to those acts and activities that intentionally seek to build bridges across differences, develop solidarity and shared ground, and promote social connection between different groups and communities.

The concept of “motherwork” is used to make sense of these women’s labour. Motherwork is the labour of mothering, and here the concept is expanded to include the community-based activities of the Swedish-Somali mothers. Mothering as a verb offers us a way of thinking about the activities mothers engage in as a practice (a doing), rather than given or natural.

I use “mother” without any assumption of a biological essence. A mother does not need to have a specific gender or biological children to be considered one. Rather, a mother is anyone who engages in the practice of mothering– the meanings we place on who a mother is shifts over time and place, and are shaped by intersecting identities.

In Denmark, fællesskab is one of the most important values of their society. It is a collection of people that are bound together by something they share in common, something they agree with, have the same view on, or an interest they share or do together.

Fællesskab can be seen in all aspects of Danish life, from foreningsliv (“association life”) which are groups of people formed around different hobbies or interests–from the classrooms, to the workplace or family life.

The issue in other cultures is that, while we think about the wellbeing of our children, we rarely think about the wellbeing of the group and what effect that has. In Denmark, this focus on the group is seen as absolutely fundamental to the wellbeing of the individual. Their entire educational system is structured on this. Danes believe children need to learn to think about others too, not just themselves. This is how we create a better society

If division is to be healed – and if, for that matter, we are to achieve the depth and persistence of public demand necessary for proportionate action on inequality, structural racism or climate change – then it will be because we begin to see how the neoliberal project engineers a society in which care for others, community cohesion, and wellbeing are all suppressed.

This may seem daunting, but there are huge grounds for hope. Our values are on our side. We need simply to assert what is most important to us and to recognise these same priorities in our fellow human beings.

“But what does the concept of belonging mean to refugees? How do refugees create feelings of belonging for themselves and foster it for others? Most interesting for us, what role does refugees’ civic engagement, such as self-organisation and volunteering, play in fostering belonging in Europe today?”

While one good deed may seem like a drop in the ocean, its ripple effect can carry immense potential to amplify in reach and impact. The more we unite around our shared vision and values, seek out and cultivate kindness and welcoming behavior at the local level, create spaces and enable diverse identities to listen to each other and reach common goals, as well as persistently share these stories of a larger ‘us’, the more likely we will succeed in diminishing skepticism, shifting narratives and realizing a future where all migrants’ rights are respected. A future in which we can all belong.

“This essay serves as a backdrop to the papers submitted for this volume. These papers cover topics ranging from motherhood-driven civic engagement by migrant mothers in Sweden, to “togetherness” oriented childhood education in Denmark, to refugee-led Covid-19 responses in Berlin and their impact on the experience of integration. As these papers draw upon a conception of belonging presented or prompted by us, we wish to describe the contours of our understanding of the term so the papers make sense in context. Our presentation is not exhaustive, but should be sufficient to the goal of making the papers comprehensible in their own terms.”

“An encompassing and embracing experience of belonging may be one of the few utopian ideals that can — and, indeed, does — exist in the world. It is a feeling of intentional togetherness that anyone, anywhere can experience mentally, physically, and spiritually—its absence can also be felt acutely. Many are explicitly made to feel that they do not belong. Still, the possibility to feel belonging exists for everyone. Belonging is a multi-faceted and beautiful experience, differentiated from diversity or inclusion in that it is something we can all contribute to–a collaborative effort requiring a whole society approach. By definition, belonging includes the agency to contribute to the evolution or definition of that to which we belong or seek to belong.”