A rebellious brand born in Barcelona sways the weight of language

How undocumented African immigrants in Barcelona have turned an othering term into a fashion brand that claims intentional identity and belonging

The seas off the coast of Spain are starting to warm up, and in a day of calm seas, migrants set out to Europe, packed tightly into light boats called ‘cayucos’. It is a difficult trip, but one worth it, especially for those experiencing acts of violence due to the rise of jihadi terrorism or ethnic violence in some parts of Africa. Last year, for the first time, three of the top five nationalities seeking asylum in Spain were African.

Already in the 90s, Spain began to receive newcomers from Africa, especially from Senegal, Nigeria, Cameron, Mauritania, Gambia, Mali, and Ivory Coast. We might be justified in expecting that a second generation, a decade or two after the first, and walking a social and economic path carved by their forebears, would have achieved middle class status, at least–potentially even hold positions of relative power in the workplace.

However few senior jobs are held by African immigrants or their children. Instead, the continuous yawning gap in the administrative process to regularize immigrants holds them back from entering the job market, and rather keeps them in a limbo that feeds “othering"1 and creates a dehumanized idea of the African community.

Though racism crucially factors in this issue, to reduce the problem to racism alone would do a disservice to understanding the broader reality of structural inequality. The political and institutional failure of authorities and policy-makers to process and “regularize” newcomers in a timely and effective manner leads to the rise of out-group identity and negative stereotypes.

Lamine Sarr came to Spain from Senegal through the Canary Islands, crossing the sea in an overloaded ‘cayuco’. He was 22 years old and arrived in Barcelona in 2006, with the dream of continuing his studies while working to pay all of his expenses. Soon he faced a different reality.

As an African immigrant, explains Lamine, once you step on European soil you have already lost. Ten years later, this story keeps repeating itself across south-European countries. I met Victor on a train from Italy to Germany in 2016. He was traveling from Verona to Breschia. We started talking and I could see a kind of release in his face from venting his frustration. Victor had been in an accommodation for refugee applicants in Brescia for two years waiting for the Italian authorities to process his asylum application. Coming from Nigeria, a return home was foreseeable as the country was not ‘categorized’ as a war zone; sporadic sectarian killings and spread violence don’t count in official assessments. His journey was more hazardous than Lamine’s; Victor was smuggled overland from Nigeria to Libya. Once in Libya he was kept in a refugee camp in inhumane conditions where, as has often been reported by investigative media, he was aware of instances of rape by police, as well as beatings and torture.

After a long and risky journey, illegally smuggled through borders and across the sea, distressed African immigrants usually face the bleak reality of limited opportunities and being seen through preconceived identities. What you have achieved in your country of origin does not hold value in this new land. Deep-seated negative perceptions of “the African immigrant” held by the existing community make it difficult for immigrants to achieve social mobility and settle into their new home. Given prejudices and the administrative setting, as Lamine describes, “When you find yourself on the street, everything is more complicated than you thought."

The only way he found to survive was thanks to Top manta. Like Lamine, many African immigrants in Spain end up working as manteros, undocumented street vendors who display their wares on blankets (mantas in Spanish) on the pavement. The wares are fakes or unauthorized replicas of music CDs, commercial video DVDs, clothing, watches, bags, etc. By selling them, they infringe copyright laws – meaning their activity is illegal and punishable by imprisonment. They usually sell on big avenues or streets where many people walk, such as on the seafront promenades, or in the center of towns. Vendors use the blankets to collect their merchandise as quickly as they can and flee when they notice the presence of the police.

It is difficult to tell when the term Top Manta became popular and part of the common language. Presumably it was born in the 90s with the boom of the CD, a costly product of an incipient technology, whose cheaper fake copies people were very keen to buy on the streets. The term Top is believed to come from a parody of the top (or hit) lists of conventional music, which implies that if a music production makes it to the blanket, then it probably dominates the tops of radio stations.

With time Top Manta has become an abstract concept that captures the variegated expressions of a broad prejudice beyond race or religion. It encompasses many conditions of some in the African immigrant community in Spain under a defined label that goes along with a sensational overtone of underlying “problems”—occupancy of streets, illegal sale harming local shops, a threat to jobs for locals. But it writes off the intrinsically human realities of migration: a person with a previous life, qualifications, no other choice than to leave a family behind, and the right to a better future.

The term Top Manta typically dehumanizes and gives an identity that propagates inequality and marginality, and traps immigrants in a vicious circle. This “othering” term predominates not only in the popular language on the streets, but also in the Spanish media. Additionally, the use of metaphorical, hyperbolic, belligerent, or alarmist language, referring to arrivals of people like a 'wave' or 'invasion' – or even an 'assault', in relation to the entry of Africans through the fences located in Ceuta and Melilla – reinforces a biased image that is institutionally embedded. “All these terms are already normalized in Spanish society,” says Lamine.

According to a report2 on Immigrationalism by Red Acoge in 2021, 20% of the information on migration analyzed in Spanish media contained such references. Every year a multidisciplinary team of professionals analyzes information on migration published in the Spanish press, the report this year looked at a total of 3,560 articles from 26 newspapers (national, regional, and independent). In addition, they carried interviews with 37 journalists and communication professionals, and 58 migrants outside the profession.

The study is quite revealing. It confirms the absence of voices of migrants in more than 83% of all the information on migration scrutinized. It also reveals the lack of use of the term 'person' in more than half of the news on migration, which contributes to the distancing of the audience with the humanity of the current migratory reality.

The predominance of sensationalist images–with a highly negative charge–reinforces the generation of prejudices. Very often, photographs about migration contain the presence of police, thus generating alarm and contributing to a narrative of immigrants as posing a danger that is being controlled or prevented by police forces.

The report warns of the dehumanization in information on migration; and how this series of repeated practices generates harmful stereotypes by combining dehumanization, criminalization, and alarmism. This negatively contributes to the political climate in Spain. The far-right party Vox, which recently won 15.21% of votes in the regional elections of Castilla-León and currently has 52 of the 350 seats in the Spanish parliament, leverages discriminatory rhetoric to justify the deportation of immigrants and attract votes.

The fact that Vox does particularly well in the South of Spain, where Spanish farmers depend on Moroccan and other African laborers for the harvest, proves how powerful the negative image of the Top Manta. Despite, in reality, needing the labor of immigrants, farmers see them as a threat and problem. According to the National Institute of Statistics in Spain,3 Immigrants in the country represent around 11.4% of the population. Some say the country needs newcomers, for instance, because it will need an extra 6m to 7m workers by 2040 to meet its pension bill.

However, the regulation process to legally include them in the Spanish census is slow and difficult. Lamine, who got his papers after 13 years in Barcelona, is living proof of an administrative labyrinth. Immigrants need to prove three years of residency in an apartment with rent and one year of paid employment in order to apply for citizenship. This means that they have to navigate the streets for at least three years without getting caught by the police. And here is where the cat-and-mouse game with the police starts. “If the police gets you and opens a criminal file, the citizenship process would take longer for those who might need to remove previous criminal records. The process is in itself a vicious circle because it is difficult to find a job without regularization but you need it to start the process,” Lamine explains.

Long processes of administrative paperwork and accommodation at asylum centers cause an unnecessary delay in the regularization of immigrants, which leads to locals thinking that migrants don’t want to work–and rather want to take advantage of social subsidies. To the contrary, they have ambitions. After years of being singled out and persecuted by the police, Lamine, together with other undocumented immigrants like Papalae, Mouhamet, Modou, Mansour and Aziz, showed their resilience to overcome a deadlocked situation. They used a network woven over years (many of the vendors knew each other from the street) to legitimize and vindicate their rights through the creation of the association Popular Union of Street Vendors4 –a feat they have managed without having a political party or an NGO behind them.

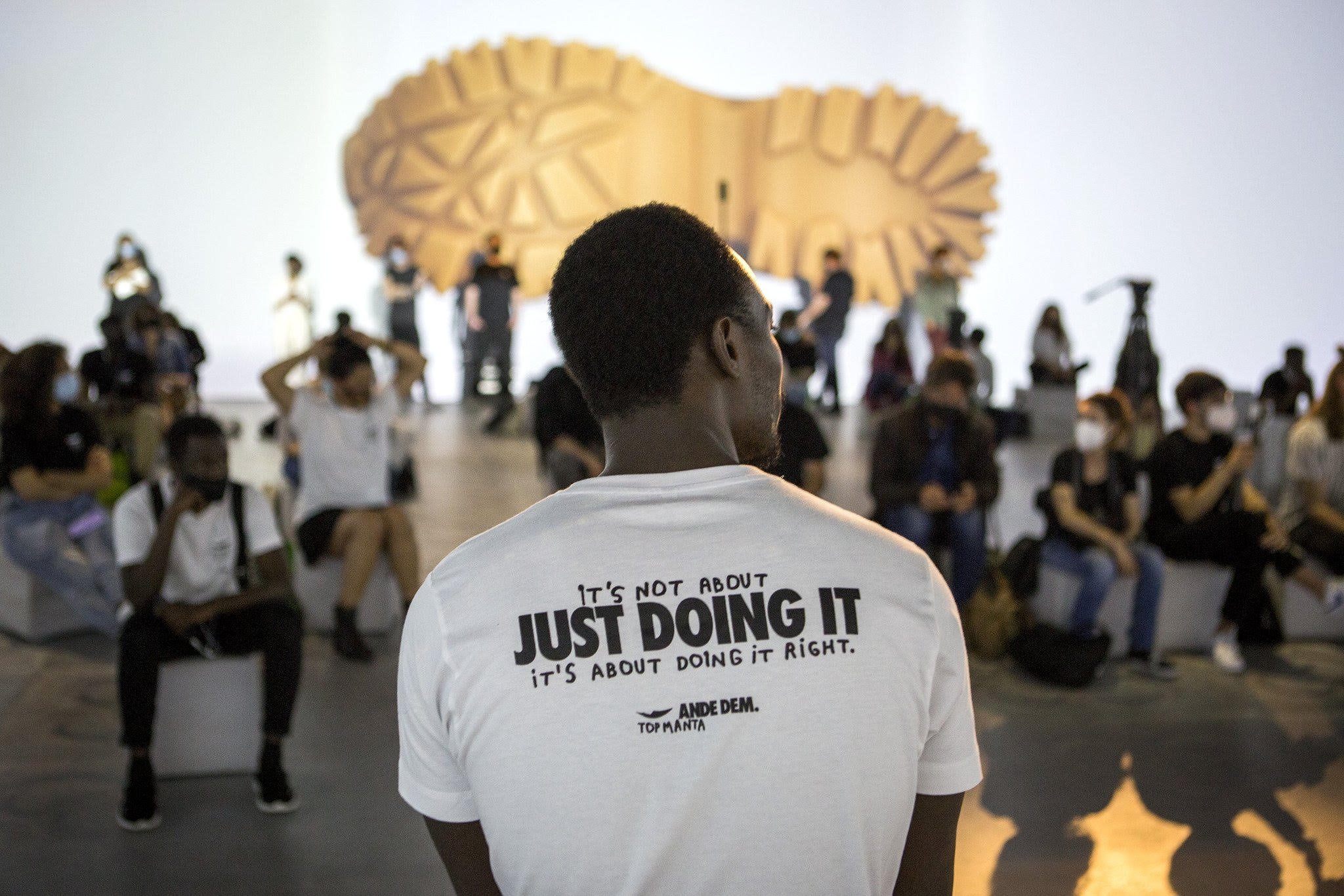

Once inaugurated the association launched a crowdfunding campaign to self-produce clothing under the Top Manta5 brand with the slogan “Legal clothing made by illegal people”. 'The project intended to create job opportunities and help the manteros achieve their dream of working legally and living with dignity,' explains Lamine, who became the brand’s spokesperson.

“But for most the project sought to disprove stereotypes and discrimination about the African community, showing their ability and talent. We want recognition from society more than from institutions.”

They decided to use the label of Top Manta for their own benefit: to dignify it and overturn the undervalued image of the African community–one that has been wrongly considered criminal and violent or simply not part of society. Top Manta had, for many years, been a crucial component of the “othering” that discriminated against their community ‘in such a way that a part of society does not consider us people, human beings’, reads their website.

In 2015 they started producing t-shirts, sweaters, and tote bags using their skills and learning screen printing techniques among friends. Thanks to the money from the crowdfunding campaign they started a screen printing workshop and opened a store in the Raval neighborhood. Slowly the clothes began gaining popularity–to the point that in 2020 the radiant Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar stood on the red carpet in Venice wearing a black mask with a tiny logo resembling a ‘cayuco’. Top Manta intends to persuade urban dwellers in Barcelona, and beyond, to wear a brand that denounces racism, persecution, and punishment, all of which the brand’s own creators experienced. Their clothes tell their story.

In 2018 Mmame Mbage, a Senegalese migrant, died ‘suffering a heart attack’ after being chased through the streets by police on a motorbike in the neighborhood of Lavapiés in Madrid. This happened a few blocks from the renowned Reina Sofía Museum. A rattled staff made a collective decision to open up the museum to the neighborhood in a unique collaboration called Museo Situado.6 The museum organizes talks and activities–conceiving a hybrid third space for thriving coexistence, and for fostering a dialogue that addresses the conflicts and desires of its neighborhood of Lapavies, including those of the African Community.

The disturbing incident deeply affected many people and was a wake-up call in the creative and artists’ community. When Top Manta approached members of the creative industry and artists in Barcelona in 2020, they didn’t hesitate to collaborate on some of their designs. Important to note that these collaborations did not exist in a national bubble, and indeed coincided with the assassinationof George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent protests on the streets of Barcelona in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in America condemning police brutality against African-Americans.

All these experiences have showcased the human capital available in a city to help one another, and the spectrum of responses to othering. One wacky, but important result of the collaboration with artists and creators in Barcelona was the presentation, in a fashion show last year, of shoes suitable to climb and run the streets. The motto of the confident new clothing line, calling to mind the origins and struggle of the creators: “It’s not about just doing it, it’s about doing it right”.

The success of Top Manta is a rebuke to Spaniards who think African immigrants do not belong. It has proved that it is much more than just a clothing brand. It is a movement–and one that is spreading to other cities; street vendors have opened a store called Pantera in the neighborhood of Lavapiés in Madrid. The store offers a solution to escape criminalization and precariousness while transforming and dignifying the meaning of the pejorative term.

“Now when you google Top Manta you get a fashion brand instead of negative news scrammed with a negative image of our community,” says Lamine proudly. “That is our greatest achievement”.

However not everybody admires Top Manta’s pluck. In 2018, The Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (SPTO) rejected the registration of the Top Manta trade name, mainly due to allegations that such recognition could legitimize what is an illegal activity that is largely based on piracy and the street sale of counterfeit products. The official resolution argues against Top Manta for "lacking the ability to be perceived by the public as a brand, but rather as a form of itinerant sale or sale on the street, mainly of imitation or counterfeit products, which usually coincide with the type of products for which it is requested". The rejection to officially register the brand came in 2018 at a time of controversy surrounding the death of Mmame Mbage.

Lamine acknowledges that they are battling against all the odds. Dehumanization is the main stumbling block on the road, but equal treatment with a rights-based approach is their goal. The biggest challenge, he explains, is the Immigration Law in Spain, whose reform is not a priority for the coalition government and which generates conditions of inequality and persecution of the migrant population. There are still around half a million undocumented persons in Spain (and 1 of 3 are underaged).

Levering a change of perception of the Top Manta, the association of vendors, together with other organizations for human rights, are actively trying to mobilize civic society to put pressure on the Government regarding immigration law. Last February they called on Spanish citizens to sign a petition promoted by the campaign #RegularizaciónYa in more than 16 Spanish cities in order to collect 500 thousand signatures on a move to exercise direct democracy. The signatures would be enough to take their request to the Spanish Congress to revise the Law hopefully in favor of all immigrants in an irregular administrative situation.

“Our association is not an ideology or declaration of principles, it just explains a life struggle for justice, dignity and a better future,” says Lamine. They want their voices to be heard to denounce a situation which affects many persons and reinforces the “othering” in Spanish society. The pandemic has brought to light the deteriorating conditions of this community without access to social protection measures due to their irregular situation. “The institutions have left us behind despite being on the front line helping fellow residents,” said Lamine.

In their request to the Government they argue the need for regularization on the grounds of access to fundamental rights, because irregularity means being in a condition of permanent vulnerability. It causes the loss of the great economic and fiscal contribution migrants could offer, and therefore wealth for the Spanish society as a whole. Irregularity prevents them from contributing to society and to their own development with dignity and in the full capacities available to them.

Regularization would be a big step, but would still need to be accompanied by a change in the narrative, use of words, and expressions that are used in relation to migrants and migration. Language needs to be harnessed to actively foster a sense of belonging for migrants.

It is time for articles to take a careful and broader approach to the migratory processes and to the reality of migrant persons–rather than summarizing whole people and experiences in words like Top Manta or manteros.

For this reason, the report on Immigrationalism makes a call “to the professionals of information, whose work as guarantors of freedom of expression and truthful and quality information makes them natural allies in the defense of human rights, as well as citizens as consumers of information.”

The reclamation of Top Manta has already partly been achieved, but the media is dragging its heels and continues to contribute to “othering”. There continues to be a notable lack of diversity in Spanish newsrooms, and an adherence to a westernist gaze that too deeply permeates the production of information. Providing a broader context, avoiding partial or incomplete descriptions, would leave no room for political opportunists to advance their agendas.

In the meantime, many others like Lamine will take the dangerous journey to cross the Mediterranean to reach Europe. A better life is their underlying credo. I wrote once about an impressive street clean up initiative in Onitsha, Nigeria, one of the most polluted cities in the world. The initiator, Chris, a graduate of the University of Nigeria, was so frustrated with the Government’s inaction about waste management in his street that he and some local boys in the neighborhood decided to take things into their own hands.

Since I wrote that article, Chris has approached me many times asking for advice to leave Nigeria for a better life that feels safer, and with more opportunities. The decision is a rollercoaster of emotions. He felt most proud when the Nigerian president promised to disband the notoriously abusive police unit known as the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, or SARS, after youngsters like him staged the biggest anti-government uprising in a generation to protest against relentless police brutality. But he has also been through many other moments of frustration and fear, staying home to keep himself safe from the under-the-radar sectarian violence on the streets.

I tried to tell him that things are not easy on this side after arrival. I am too ashamed to reveal that many well-qualified young people are unwillingly forced to turn to street vending in Spain. I asked Lamine whether his fellow Africans are aware, before leaving, of the reality awaiting them. And if so, why they are still willing to take the risk? He replies with a smile that “life is all about adventure. If they want to try, they should.”

The legacy of colonialism continues to have a social, economic, and political impact such that many Africans, whether for professional opportunity or for access to resources or for the chance to live with greater personal freedom, are left with no choice but to look to make a life in another country.

In another conversation Lamine told me, referring to the western world, “stop exploiting Africa and let us choose the leaders we want. Africa is not a continent, it is a paradise with almost everything, community, culture and natural resources. Why would people like to leave it?”

But if they do, Spanish society has to be prepared to “humanize” that difficult decision and all that it implies, and accept their right to belong. I can't think of a better way to start than by supporting the reclamation of the term Top Manta by wearing one of their pieces–true clothing made by fearless, confident people.

Author bio:

Susana F. Molina is the founder and editor of The Urban Activist, an independent global nonprofit publication committed to advancing urban progress. She holds an MBA from Universidad de Oviedo (Spain), was part of the Erasmus Program in Germany and attended The London Business School. After a long international exposure in the corporate finance world, and being passionate about cities, she launched The Urban Activist to energize creative approaches to pressing urban issues. She also manages the grassroots project Denk Mal Am Ort (Think on the Spot) in Munich engaging citizens to pay tribute, at original sites, to individuals who were persecuted during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany.

Photograph credits: