Artist and facilitator Alaa Alsaraji on Mapping Sanctuaries within the British Muslim community

Alaa Alsaraji is a visual artist, designer, and creative facilitator. Through her creative practice, she aims to explore themes such as belonging, reimagining space, and community, predominantly using the medium of digital illustration. The Democracy and Belonging Forum’s Evan Yoshimoto met with Alaa to discuss her project Mapping Sanctuaries where she explores the notion of “safe havens” and the spaces that exist between isolation and belonging within British Muslim communities.

Hi Alaa! It’s lovely to speak with you today. In Mapping Sanctuaries, you explore the notion of safety and the spaces that exist between isolation and belonging within British Muslim communities, which you call “safe havens.” The first question I have for you is, what does belonging mean for you, and how does Mapping Sanctuaries document this?

As an immigrant who has lived in three different countries and vastly different cultures, defining my own sense of belonging has been a central question throughout my life that has never had a full answer. But through my work, I try to understand it from different lenses of other people's experiences.

In Mapping Sanctuaries, I interviewed British Muslims from different backgrounds about where they feel a sense of belonging to understand how they define it. I learned that belonging is not necessarily felt within a specific space one can pick out. It's more of a moment in time, even if it’s temporary, where it feels normal to be yourself without an explanation and without a defensiveness you have to bring to the table because you're met with hostility or preconceived notions of who you are.

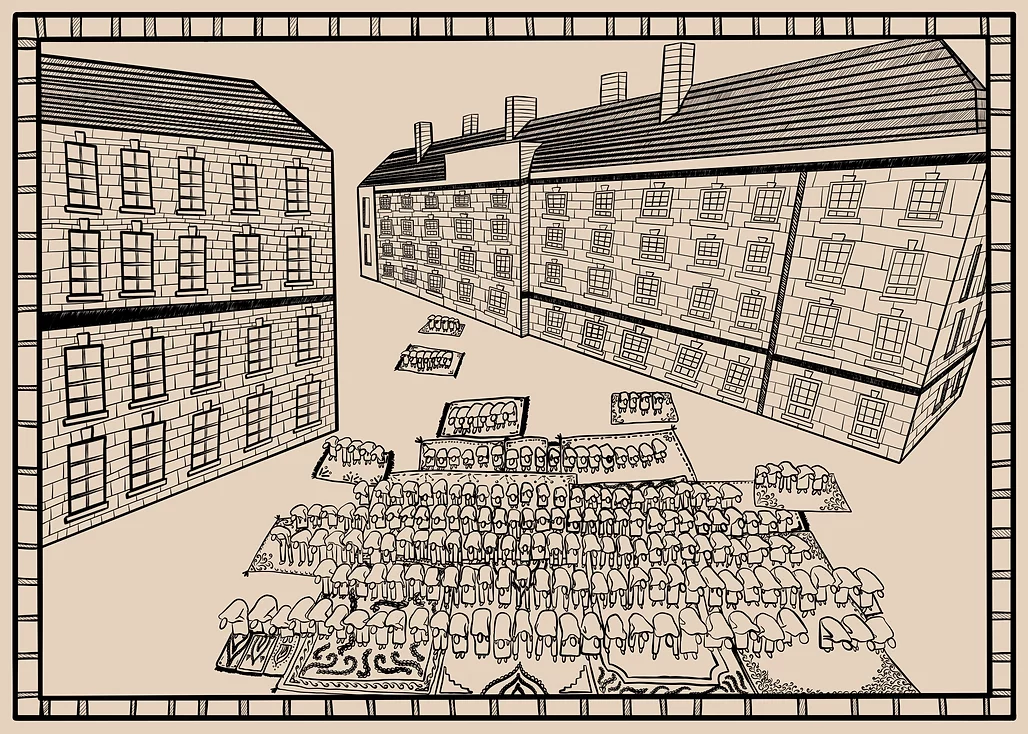

Mapping Sanctuaries: B.C.C. British Community Centre

What makes a space a sanctuary? What are the elements of that? Did anything surprise you about the spaces that people made their safe havens from?

All of the participants had very different perceptions of what makes their space a sanctuary. For some, it was the element of being able to be unapologetically yourself. For others, it's that feeling of being the majority within a country where you're a minority. A personal example of a sanctuary for me would be Green Steet in London where I live and the predominant demographic is South Asian and Muslim. Here I feel I can be myself. I feel safe. For some people, they could not define anything beyond their own bedroom or beyond their own kind of living room because everything else then starts being a negotiation of different elements of who they are. It's only in their own domestic space that they feel they are in a sanctuary.

I think the most interesting one was actually at the London School of Economics, which at first doesn't sound like a sanctuary for a lot of different people. But it was a particular street within the campus that many of the students of color, in particular the Muslim students, took over and claimed for themselves. This former student had sweet and character-forming memories of being in a space with like-minded people who made them feel belonging in an academic institution setting that felt otherwise very hostile. For them, it was about being unapologetic and being able to say this space belongs to us. Not officially or in any kind of material way, but in having a presence and taking up space together way. Sometimes the determining factor of what makes a space feel like a sanctuary comes down to numbers. If there are enough of your people within a particular space, you can have that feeling.

There was a similar example within Cambridge university, which is known to exemplify a lot of exclusionary behavior. There was one common room for students with one sofa where women of color were frequently meeting and spending their time. This was their space. They convened there. It was really nice to see that even within the places you would not imagine feeling like a sanctuary, this feeling of creating your own sanctuary or safe haven was possible.

On your website, you say that ”From the private to the public, these spaces are often improvised and built out of necessity, yet they create a sense of belonging and safety, where multiple identities can exist as one.” Are sanctuary spaces inherently solitary spaces or do they foster connection?

It really depends on each person. For the ones that selected their own bedroom or domestic space, it was about being in a solitary space and in control while living in a world where they felt largely out of their control. In these spaces, they did not have to extend energy toward dispelling perceptions of them before they even had the chance to be heard.

For other people, sanctuary spaces were about fostering connections, including with those that held different identities than themselves. For example, on Church Street (image below), there was one person who frequently visited a particular market where Arab and North African cultures collided. It was the one place in London where she felt seen and connected as a Black Arab person. The market offered a unique mixture of people and culture that they would not necessarily find in London’s Arab spaces alone.

Mapping Sanctuaries: Church Street/Alfayez

Another participant talked about their mother’s living room as an example of a sanctuary space built on fostering connection. It was there they were able to observe their mother and her friends show their true selves, which is often extremely different from who they had to be while out in public, especially as an elderly Muslim wearing a hijab. In those living rooms, when the mothers come together with one another, they would go wild in a way that no one would believe. The shisha comes out. The music comes on. It’s beautiful to see.

Mapping Sanctuaries: Mother’s Living Room #1

What does it mean to have and consciously recognize multiple identities in these safe havens? How might that be a strength, as opposed to a weakness? (And are there any challenges community members faced in sharing and holding these multiple identities?)

I think it depends on what is being sought out. In London, there are Mosque initiatives that create space for queer Muslims and non-binary people They truly bring voices in from the margins and center them in how they practice their faith and understand scripture. A lot of this is about relearning and changing how we question institutional authority. Their events are usually quite popular.

With respect to challenges community members face in sharing and holding these multiple identities, there's always a struggle with how are we perceived within the wider Muslim community and how the wider British media utilizes our narratives to scapegoat us. It’s easy for our narratives to be twisted and then used against our community. Within my work, I have to be really careful with how to talk about nuanced issues around identity to make sure that it is not being used as a political tool in a negative way within British institutions and media outlets. It’s a lot of extra work that needs to be done that we should not have to be doing.